What follows here is a record – letters, testimonies, personal accounts – preserved from the first century after the Fracture. I have gathered them, not to impose order, but to remember what order cost.

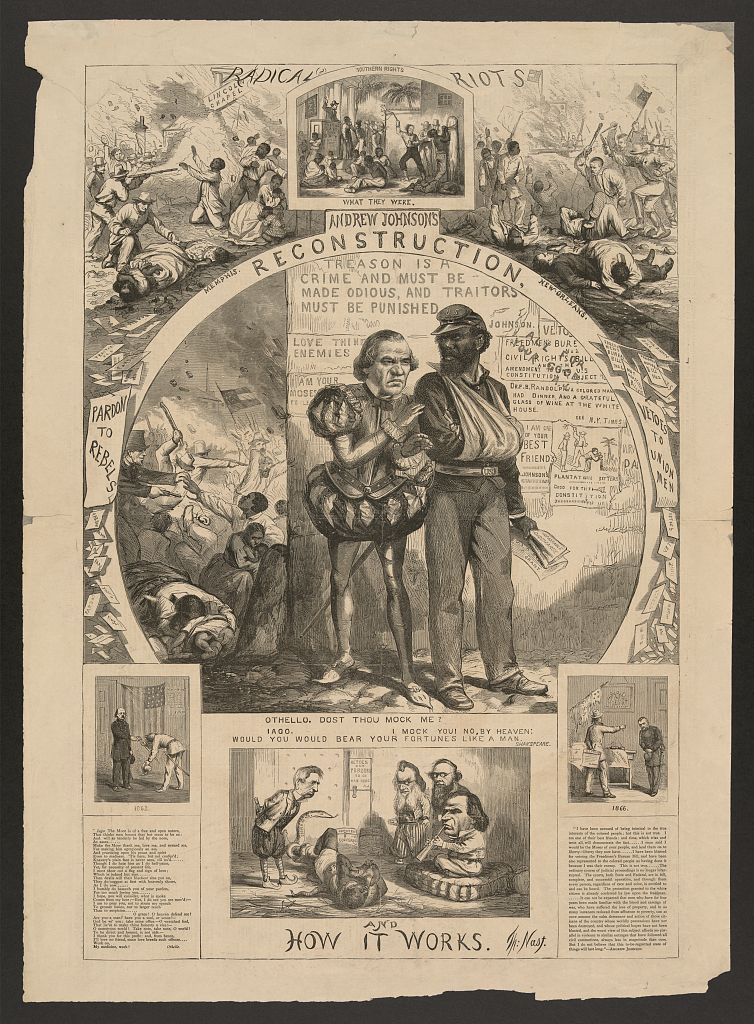

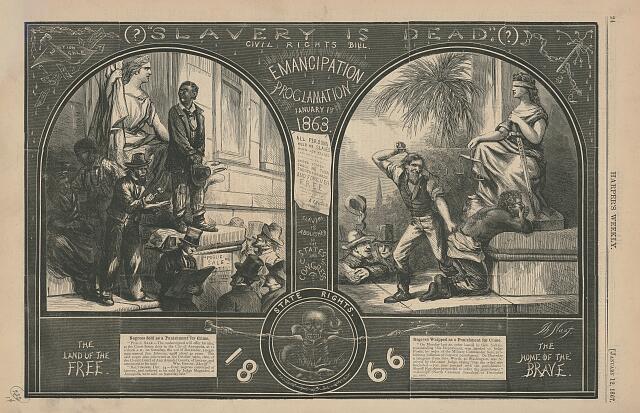

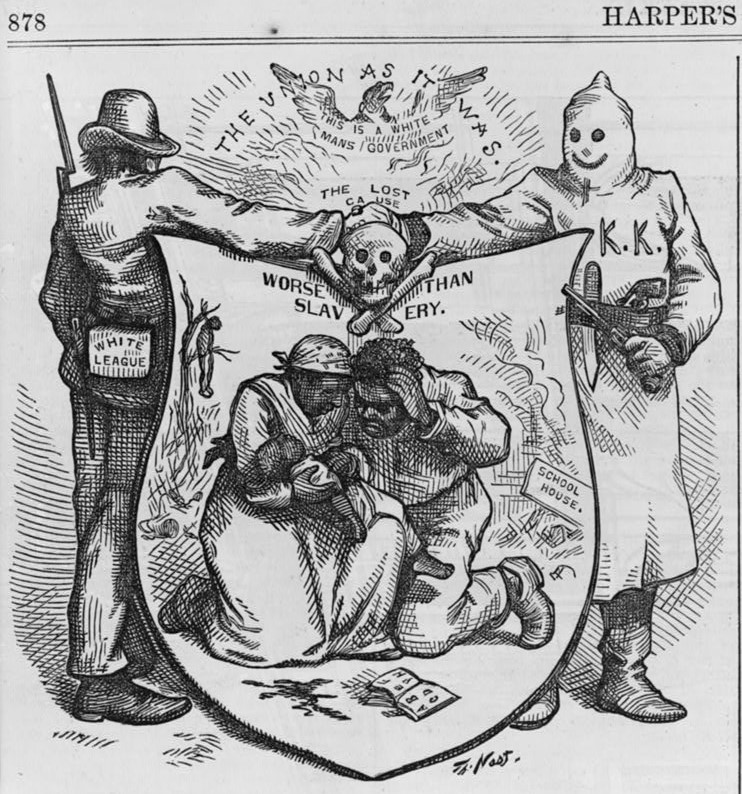

In the histories, the Fracture marks the year the old United States failed. When the federal government abandoned Reconstruction, the nation split along the same fault lines it had once bled to mend. Six sovereignties arose in its place: the Northern Coalition, the Confederate Southern Territories, the Western alliance, the Pacific Freehold, Cascadia, and the Commonwealth of New Alaska. What began as a political secession ended in national collapse. The language of freedom splintered into dialects of survival.

To those that lived through this period, it wasn’t history. To them, it was simply a breaking: of union, of nation, of faith. They did not know what would arise from the ashes. The Underground Railroad was reborn, carrying the formerly enslaved out of the Confederated South and as far north and west as they could go. What began as a flight to safety became a great migration, an exodus that reshaped the continent and the generations that followed.

To the people we are chiefly concerned with here–the settlers, survivors, and kindred who would become New Alaskans–the old republic had never meant mercy. They had only known the chasm between the nation’s promise and it’s practice. For them, the Fracture was not the end of a country but the beginning of a reckoning: the chance to build a freedom that was lived, and not merely declared.

The early decades after the Fracture were called the Age of Repair, as people began the long, ordinary work of mending what empire had tried to ruin. They built schools rather than prisons, planted law in their soil, and argued–tirelessly–over the meaning of freedom. From their quarrels and their care, the Commonwealth of New Alaska was born.

Much has been written of its founders: Sinclair, Valeria, Makakuk, Greene, Jenkins, and True. Yet history, as it is taught, often forgets the quieter sovereigns–the teachers, the children, the constables who carried ledgers instead of guns. This archive belongs to them too.

I was raised among the descendants. The Aurum sings in my bones too. My grandmother kept a single page from the charter with her always, folded in the pocket of her skirts–Article III: On the Sovereign Child. The paper was soft from years of handling, the creases torn and repaired, torn and repaired again. She said it wasn’t for show; it was for remembering. She taught me that we become and remain free by keeping each other whole. This work is my attempt to honor those words.

The records that follow are drawn from the living archive of the Commonwealth — letters, ordinances, testimonies, and journals preserved across nearly one hundred and fifty years. They have been copied, recited, and recopied again; not out of reverence for paper, but for the truth the memory requires muscle.

I do not collect these pages because they are rare. Far from it. They are everywhere–in kitchens, in schools, in the hands of children tracing their first letters. I gather them to show what endurance looks like when it is properly kept.